St. Francis Frescoes

The Life of St. Francis of Assisi

Have you seen the paintings of St. Francis’ life scattered throughout the halls and welcome space of the church? When Father Steve Kluge (who donated the paintings) was in residence at St. Francis, he would present the meaning of these bibliographical paintings. As he would point out, it was St. Bonaventure, who was a theologian and bishop and considered a doctor of the Church (the Seraphic Doctor), as Minister General of the Order, starting in 1257, who wrote the “official” hagiography of Francis between 1260 and 1263, to show that Francis was another Christ. An earlier biography of Francis by Thomas of Celano was destroyed by order of Bonaventure. The Italian artist Giotto di Bondone, who lived from 1226/27 until 1337, is reportedly the one who painted the frescoes between 1297 and 1300. It is generally under dispute whether Giotto painted them or just designed them. Here we present a very brief overview of the frescoes and what events they depict in Francis’s life.

While the friars are no longer in residence at St. Francis of Assisi Parish, their presence lingers in the hearts and minds of the parishioners who continue the Franciscan charism. The life of Francis depicted in the Giotto frescoes throughout campus reminds us of our continuing role as Franciscans, dedicated to the teachings and example of our patron. Through the inspiration of St. Francis and the example of his friars, we remain devoted to the way of Francis.

The first image is an ‘homage of a Simple Man’ showing a man spreading his cloak on the ground before Francis because he believed that Francis would soon do great things and thereby should be honored by all. This first scene takes place in front of the Temple of Minerva, at the Piazza Commune, which is still in Assisi to this day. The rose window between two angels at the top of the temple is not historically accurate, but may symbolize his conversion. This conversion is made evident pictorially by the placement of the halo around Francis and perhaps by his crossed hands as if they are bound. One can see that this event takes place before his conversion, as evidenced by his choice of nice clothes. The garment between Francis and the simple man, whose facial expression suggests anxiety over how Francis will receive this gesture of kindness, joins them together and might symbolize Christ’s tunic without seam.’ (John 19:23).

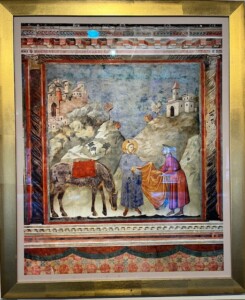

The next image depicts Francis meeting a noble but impoverished knight, and he shows respectful compassion for poverty, immediately removing his cloak and giving it to the knight. Devotion to St. Martin of Tours was extremely popular in the 1200s. Legend has it that St. Martin, coming upon a poor man, gave him half of his cloak. Bonaventure, in seeking to make Francis greater than Martin, has Francis give his whole cloak to a poor man. Francis stands ‘centrally haloed’ between state and church, symbolized by the buildings on the left and right. Francis is facing toward the church, turning his back on the state and all it represents. The horse, symbolic of wealth, power, and strength, is seen bowing its head at the gesture, almost as if giving its assent.

The third fresco shows Francis kneeling before the crucifix. As he began to pray, he heard a voice coming from the cross itself, which said to him three times, “Francis, go and repair my church, which you can see is completely in ruins.” In Bonaventure’s biography, the start of Francis’ conversion begins with the command of the San Damiano cross: “Rebuild my church which is falling into ruin.” Here we have that scene, taking place in the ruined church with a wonderful representation of the San Damiano cross to Francis’ right. As Father Kluge pointed out, ”Interestingly, Francis is in a place much darker than the rest of the church, perhaps to suggest how Francis misunderstood this command. The church needing rebuilding was not an edifice, but the relationship among the people that make up the church. In the painting, Francis’s hands are raised and poised in awe, wonder, and surprise, and perhaps even surrender. His eyes meet the eyes of Christ in the crucifix standing behind an empty altar, while a deep blue dome looms above to suggest the opening of the heavens.

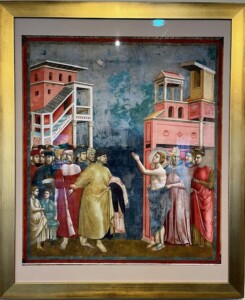

The 4th painting depicts when Francis stripped himself of all his clothing and gave it back to his father and said to him, “Now I can say with all truth, ‘Our Father who art in heaven.’” Francis is contextualized within the emerging merchant economy of the thirteenth century through the garments worn by those in this scene. Francis stands between two groups: the merchants with his father, and the clerics (note the tonsure). The facial expressions of both groups suggest wariness and incomprehension. Unlike the fresco of the Homage of the Simple Man, in which the cloak connects the two, nothing connects Francis and the mInsteadts. Instead, Francis now stands enfolded in the Bishop’s cloak: he is now under the protection of the Church. His eyes focus on the right hand of the Father appearing in the sky. The graduated blue hues in the sky might suggest a transition from the concrete earthly world to the mystical world of heaven.

The next fresco is called the ‘Dream of Innocent III.’ The Pope at the time, Innocent III, had a dream as if the Lateran basilica was about to fall, but saw a poor, little, modest, and unassuming man leaning against it, holding it up so it would not fall. Francis traveled to Rome to have his ‘rule of life’ for the friars approved by Pope Innocent III. The Pope declared he needed to sleep on it. That night, Innocent III had a dream that the church, symbolized by the Lateran Basilica, was prevented from falling by a man wearing a brown robe with a cord belt with three knots. In this painting, we can see the Pope sleeping while still wearing the trappings of Papal wealth and power: the fine robes, the crown, the gloves. As Father Steve says, “What is most interesting to me about this fresco is that Francis, holding up the tottering church, is depicted as firmly standing within its foundation: something Francis insisted on for his followers. Innocent III granted Francis’ request to live the Gospel.

‘The Confirmation of the Rule by Pope Innocent III’ is the 6th of the frescoes. The pope approved the rule and granted Francis and his lay brothers tonsures, as well as the right to preach the Word of God and offer repentance. In a well-appointed Papal audience room decorated with lavish and intricate tapestries, Innocent III gives the Rule of 1209/1210 back to Francis. The pope is seated on the papal throne, raised higher than all the others. Bishops and scholars surround him. Francis and some of the friars are now tonsured, signifying that they are now clerics, while the lay brothers are not. The brown tunics contrast with the rich colors of the Pope, bishops, and scholars on their right, as well as with the tapestries that enclose them.

Francis, to bear witness to the Christian faith, wished to enter a great fire with the priests of the Sultan, but they all fled. This event is painted in the 7th fresco, “The Trial by Fire Before the Sultan.’ In 1219, wishing to end the Crusade called by Pope Honorius and to die a martyr, Francis went to the Holy Land to convert Sultan Melek-el-Kamel. Francis challenges the Muslim holy men to enter the fire with him to prove whose faith is genuine. “At the left,” pointed out Father Kluge, “the Muslims retreat at the challenge, with one even extending a hand as if saying, ‘No way, not me.’” Standing in the center is Francis, pointing both to the fire and himself, with his hand on his heart. This image may suggest the burning desire for martyrdom deep within his heart, as well as his conviction of the fire of God’s love and graciousness. This scene captures the moment when Francis offers to enter the fire by himself if the sultan and his people convert. Like the Pope, the Sultan is seated on a high throne and seen rejecting Francis’s offer. If looked at closely, Francis is painted slightly lower than all the other characters in the fresco, perhaps to suggest his call for his followers to be ‘minores.’

In one of the most famous stories of Francis, Blessed Francis asked that a manger be prepared in memory of Christmas. He then preached about the nativity of the ‘poor King’ in the fresco called ‘The Manger Scene at Greccio.’ “By placing this scene in a church, Giotto offers a revision of the texts of Bonaventure and Celano, which place the event outdoors,” said Father Kluge. Francis and the Child, wrapped in red, the color of martyrdom, are central, with Francis dressed in the robe of a deacon, assuming the posture of the Virgin. Father Kluge noted, “The layman above Francis’ halo might symbolize St. Joseph, and notice the silver highlights suggesting the start of illumination.” Other symbolism includes the singing friars: the chorus of angels, the three laymen in front of them: the Magi, the three clerics to Francis’ right: shepherds. Notice the back of the San Damiano cross, as if to remind us that the crib and the cross go together. The manger, the animals’ feeding trough beside the altar, reminds us that the bread becomes the Body of Christ in the Eucharist.

As Francis was on his way to Bevagna, he famously preached the Gospel to the birds. This is the simplest of the fresco prints we have here at St. Francis, called ‘Preaching to the Birds.’ Bonaventure writes that Francis did indeed preach to the birds, fulfilling the scripture that says, “all creation waits…in hope that creation itself will be set free from its bondage…and will obtain the freedom of the glory of God.”(Romans 8:19-21). Father Kluge says, “Here we have Francis, bowing toward the birds and by extension the earth, slightly left. His hands, centered, are raised in blessing. Always barefoot, it’s as if Francis wants nothing to separate him from the earth. What is interesting to note is that in none of the frescoes are the poor pictured, except in the symbol of Francis. Francis’ biographer, Donald Spoto, in his book ‘Reluctant Saint’, reminds us that to the people of the Middle Ages, sparrows symbolized the poor.”

An ill Francis dismounts from the donkey and intercedes for a man dying of thirst, as shown in “The Miracle of the Spring’ fresco. Here we see Francis kneeling, hands raised, in a prayer of intercession. “This is the first time that Francis is shown above the other characters in the frescoes,” says Father Steve. To his left, we see two friar clerics wearing sandals looking at each other in wonder. The smiling donkey, knee in an almost genuflection posture, looks at the man, prostrate, drinking from the miracle water flowing from a rock. “Maybe,” posits Father Kluge, “the artist is suggesting that the laity, the poor, are dying of spiritual thirst. The rock reminds us of Moses in the desert, and the water is symbolic of the water flowing from the side of Christ and baptism. Perhaps the mountain is LaVerna?”

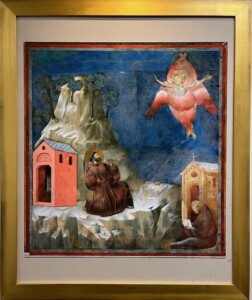

While Francis was praying, he saw Christ in the form of a crucified Seraph who impressed on his hands, his feet, and his right side, the stigmata of the Cross of our very Lord Jesus Christ. Shown in the painting known as “The Saint Receives the Stigmata on Mt. LaVerna.’ This painting is the climax of all the Giotto frescoes. On La Verna, Francis prayed, “Who are you, O Lord, and who am I?” As Father Steve notes, “Francis’ body is central and seems twisted, his hands raised in prayer, awe, surprise or surrender, his eyes focused on the seraph, and a crucifix painted in another bay, and connected with him by the rays of light/grace. We can see the marks on his hands, feet, and side. Once again, he is placed in a higher position than the other friar, seen reading, completely unaware of what is taking place. Again, we see the motif of the entire mountain wrapped in illumination, with seven trees in full bloom representing the gifts of the Holy Spirit.” He adds, “Now faded, I can’t help but wonder if the face of the seraph was painted in the image of the face of Francis as if to answer the saint’s prayer, ‘we are now one.’”

The moment of the saint’s passing is shown in ‘The Death of St. Francis.’ “It is said,” says Father Steve, “a brother saw his soul ascending to heaven under the form of a most beautiful, radiant star.” Francis is lying dead on a wooden board, his face is peaceful, his body seems relaxed, and he is surrounded by clergy, friars, and other mourners. The clergy in white surplices, their Franciscan habits seen, hold candles, directing our eyes upward to the image of Francis in glory. The friars are in mourning, seen weeping, touching him, holding his hand as if they don’t want to let him go. “From our perspective,” says Father Steve, “we too are part of that group.” Francis, in glory, still with the wounds of Christ, is seen accompanied and surrounded by angels.

‘Lying dead in the Portiuncula, an educated man named Jerome, with his own hands, inspected the hands, feet, and side of the Saint.’ This image is depicted in “The Verification of the Stigmata,’ the penultimate fresco here at the parish. “If we start at the top,” points out Father Steve, “we can recognize that this is the reverse perspective of the Manger Scene of Greccio. During his funeral, Francis remains on the wooden board, while the knight/scholar Jerome places his finger in the wound in Francis’s side, calling to mind the Gospel passage in which Christ invites Thomas to put his fingers in his wounds; thus relieving his doubts. As Francis knelt in front of the San Damiano crucifix, so now Jerome kneels in front of the Saint, seeing in Francis the mirror of Christ. A man in red beckons us to see, while the man in red on the left, with his back turned, reminds us that he is of no importance. Christ’s image looks at the dead body of Francis. On either side of the crucifix, we see the Enthroned Madonna and Child, and St. Michael the Archangel. Francis had great devotion to both.